Our History

Edward S. Allen, an ISU math professor, is credited with establishing the affiliate. Click here to read more about the civil liberties and social justice work he did along with his wife, Minnie Allen.

The only other ACLU state affiliates were based in urban centers: Boston, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The enlightened creation of a dedicated civil liberties presence in Iowa was sparked by an unsuccessful attempt to repeal the Iowa criminal syndication law. This law raised concerns because it was being misused to prosecute dissenters who spoke out publicly against the government.

So what was then dubbed the Iowa Civil Liberties Union (ICLU) was organized. It wasn’t until 2006 that the group was renamed the American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa to better reflect its more interconnected working relationship with the national organization.

Here is a brief history of our affiliate with an emphasis on legal cases, for which we have the most documentation.

1930s

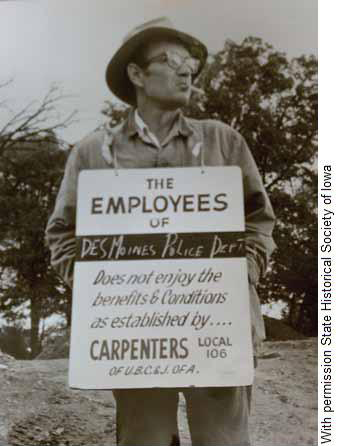

In the early years of its existence, the ACLU of Iowa concentrated on the right of the still-young unionization movement. It succeeded with two key legal victories.

In 1938, Maytag workers with the United Electrical Radio and Machine Workers Union went on strike in Newton to protest a 10 percent pay cut. Dozens of people were arrested for "criminal syndicalism," a 19th-century crime that was a thinly veiled attempt to silence those advocating social and economic change. One of the leaders, William Sentner, was singled out and actively prosecuted. He was fined what was then a whopping $2,500 or 750 days in jail. With the legal assistance of the ACLU, Senter’s conviction was appealed and reversed in a unanimous decision by the Iowa Supreme Court in 1941.

A year later, five Communists were arrested in Sioux City at a public meeting and charged with criminal syndicalism. They were defended by ICLU Board member John Denison. The grand jury indicted no one.

One of the ACLU of Iowa’s first legislative victories was in 1935. State Representative Bourke Hickenlooper, in February, introduced a bill that would require a loyalty oath of all Iowa teachers. This was popular legislation nationally at the time, which was seen as a method of somehow ferreting out communist sympathizers. The bill eventually died a quiet death in legislative committee.

1940s

In the post-war era, anti-communist hysteria began to grip America, and Iowa was no exception. The ICLU fought against loyalty oaths. And also—surprisingly in such a predominantly white state—it managed to help deal an early blow to racial discrimination.

In 1948, more than a decade before other lunch counter sit-ins gained attention, the remarkable Edna Griffin of Des Moines and others staged a lunch counter sit-in at the downtown Katz Drugstore. Katz was a notorious chain for its blatant policy of not allowing black customers to eat at the lunch counter with white people.

On July 7, Griffin, holding her baby daughter, went with John Biggs and Leonard Hudson to the Katz drugstore to order ice cream. The manager refused to serve them, saying, "It is the policy of our store that we don’t serve colored."

The Polk County attorney and ACLU pursued the case legally. The Katz manager was prosecuted under Iowa’s only civil rights law at the time, a criminal statute prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations. An agreement was negotiated to end the discriminatory practice.

1950s

The civil rights movement began to sweep the country. The ICLU’s crowning achievement of this decade came with an anti-racial discrimination suit in 1954 with Amos v. Prom.

This action was brought under the Iowa Civil Rights Act against the corporation, Prom, Inc., which operated the Surf Ball Room in Clear Lake. Following Prom’s corporate policy, ballroom managers refused to admit several black couples to a performance by Lionel Hampton. The ICLU filed a friend-of-the-court brief with the federal court, successfully arguing for a broad construction of Iowa’s Civil Rights Act.

1960s

In 1965, we also helped fight successfully for the abolition of the death penalty in Iowa—and remained devoted to the cause, working with many others for a successful defeat of an effort in 1995 to revive the death penalty in Iowa.

Throughout the 1960s, the ICLU took a strong lead in fighting for freedom of expression, culminating in the "black armband" decision, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Schools.

In 1969, three Des Moines students changed the course of student freedom of expression by insisting on their right to support a truce in the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands to their public schools. Mary Beth Tinker, age 13, John Tinker, 15, and their friend Christopher Eckhardt, 16, wore black armbands to their Des Moines high school and junior high. They were suspended.

The ICLU approached the families and helped them file suit in U.S. District Court, which upheld the school’s decision. Eventually, the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in the students’ favor. The U.S. Supreme Court set a new benchmark for student rights, saying, “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

1970s

We were on the forefront of the national due process revolution as activists fought to make sure that the American legal system worked for all.

Our 1974 Alsager case is an important example. Filed against the Polk County Juvenile Court, Alsager resulted in a dramatic overhaul of America’s juvenile justice system that still remains in place today.

Charles and Darlene Alsager, represented by the ICLU, sued over the termination of their parental rights to five of their six children, ranging in ages from 10 to one. The children were removed for neglect, and for the next six years, several were back and forth from their parents to foster homes to potentially adoptive parents. The federal appeals court held that the state had to have a clear standard, with adequate notice and very substantial cause, to terminate parental rights.

In 1976, the ICLU filed the first lawsuit for Iowans seeking the right to marry a partner of the same sex, making it perhaps the first organization in the state to sue on behalf of same-sex couples. We filed a petition, albeit unsuccessful, on behalf of Tracy Bjorgum and Kenneth Bunch, two men who were denied a marriage license in Polk County. The case was a good example of how, in much of our work, a battle may have been lost but not the war.

1980s

In the 1980s, the ICLU turned its attention to gender equality in the workplace with large-scale discrimination suits. We achieved court victories that paved the way for modern-day employment discrimination suits.

We also successfully proposed and lobbied in the Legislature to secure laws protecting students from unreasonable and overly invasive searches. We worked to assure freedom of student publications from arbitrary or over-reaching censorship by school administrators.

Because of our efforts, Iowa is one of only a handful of states where student journalists are free to publish with the scrutiny of their journalism teacher rather than the principal. Drug testing without reasonable suspicion became a national issue, and the ICLU successfully litigated and lobbied for state protections of privacy and due process.

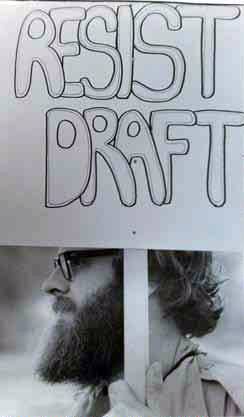

In 1984, two young men were singled out for a selective service prosecution purely based on their public defiance of the draft. The ICLU attorneys argued their case all the way to the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court. Rusty Martin and Gary Eklund were charged with failure to register specifically because they had reported their opposition directly to the draft board in protest. The U.S. Court of Appeals rejected their arguments that selective prosecution violated their right of protest, and the U.S. Supreme Court denied review.

Later, in 1989, the ICLU took a nationally heralded case, championing privacy for cordless telephone calls in what became a national issue. We represented the Scott Tyler family in a suit brought after warrantless eavesdropping on their cordless telephone calls. The case received a great deal of national media attention, and although the Eighth Circuit Court ruled that there was no expectation of privacy in cordless telephone conversations, lawmakers disagreed. Soon afterwards, Congress extended statutory protection to electronic communications. The communications industry subsequently responded by encrypting transmitted voice signals.

In 1985, in a lawsuit against the Central Community School District of Decatur County, we started the first in a long series of cases challenging the practice of including an official Christian prayer at school graduation ceremonies. With representation from the ACLU of Iowa, the Grahams prevailed, but they faced fierce reaction in their own community, as did the Skarins a decade later.

We continued our work against discrimination based on sexual orientation when we defended a group organizing a gay celebration. Its member records were seized in a raid by law enforcement agents.

1990s

During this decade, the ICLU took on the fight to prevent the restoration of the death penalty in Iowa. We prevailed despite the governor’s support of the death penalty.

The organization also worked successfully for legal protection of AIDS victims and the confidentiality of AIDS test results. Another victory came when we successfully represented a state worker who sued the state for job discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, even though no specific law made such discrimination legal.

The ICLU also began a string of cases dealing with jail and prison conditions. We successfully sued a sheriff in northwest Iowa over the treatment of prisoners, nearly bankrupting ourselves in the process.

Another major lawsuit stopped the religious indoctrination of Iowa prisoners, who were being forced to accept Christ to complete a mandatory drug treatment program.

One ICLU lawsuit forced a county to hold a legally required election on gambling.

The ICLU also successfully campaigned against the indiscriminate and inept use of ion hand scanners, which checked skin surfaces for traces of drugs by security and law enforcement. The highly inaccurate scanners resulted in innocent citizens being accused of illegal drug use.

In 1990, we took on abusive law enforcement seizures, as in the case of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources permanently seizing a fisherman’s boat and motor when he was cited for the simple misdemeanor crime of fishing with a net. We fought unfair seizures such as this one in the press, the courts, and the legislature until a reform law was adopted.

2000s

The ACLU of Iowa continued to take a wide variety of cases. We handled cases and legislation as diverse as free speech in malls and festivals, restoration of voting rights, flag desecration, school prayer, official religious displays and monuments, improper and abusive conditions and medical care in prisons, domestic surveillance, infiltration of peace groups, automated traffic enforcement, voting and voter registration rights, rights of landowners to sue animal confinements, coerced confessions, the right to bail, same-sex marriage, vehicular searches, rights of non-English speakers, disproportionate minority sentencing, student privacy, and rights to parent. The affiliate has enjoyed a great deal of success in these efforts.

Some of the cases have been horrific, as with the 2001 case when the ICLU successfully sued on behalf of a woman who was held in jail, strapped spread-eagled and naked, on a restraining board, in front of jail monitors. And we’ve been inspired by the courage of our plaintiffs. In 2002, Woodbine Community High School sophomore choir students Donovan and Ruby Skarin filed suit against the Woodbine school district and school board. The students claimed singing of “The Lord’s Prayer” by the high school choir at the school graduation ceremony and rehearsals was a violation of the separation of church and state. The district court ruled in favor of the Skarins, but that didn’t make living with their very public convictions in a small town any easier.

We have not been afraid of unpopular causes, defending even the most ostracized members of society to make sure they are assured due process. In 2004, for example, we helped fight a case that found that due process was violated when jail officials subjected pretrial detainees being held under Iowa’s sex offender commitment laws to conditions usually reserved for prisoners receiving institutional punishment. Much later, the case would finally settle with the state establishing a new facility specifically for the detention of sex offenders and others under more appropriate conditions.

That same year, we took on the unenviable task of challenging a new state law that prohibited many sex offenders from sleeping within 2,000 feet of a school, day care, or registered childcare provider. Geographical analysis showed that almost no housing for sex offenders would be preserved under this law, resulting in many offenders sleeping away from their families, under bridges, and in rest stops. Law enforcement and legislators eventually responded by scaling back the law.

In 2009, we were heartened by the victory of Varnum v. Brien. The ACLU of Iowa participated as a friend of court in the legal coalition that fought for Iowa’s landmark marriage equality decision extending the right to civil marriage to same-sex couples. We authored and submitted two briefs in the process, including the inspirational “Iowa Courage” brief.

Throughout every decade, we have litigated cases, pushed for legislation that promotes civil liberties, and helped defeat many proposals that might have become law if not opposed by the ACLU and its activists.

Our Iowa affiliate has been especially proud of its record of defending free speech rights for all, regardless of their views. The ACLU of Iowa has defended the First Amendment rights of a wide variety of groups, including anti-choice activists, evangelical Christians, draft protesters, hog farmers, peace activists, homeowners, artists, veterans, rock musicians, union workers, students, and probation officers.